Foam Magazine #61- Talent

An Article on “Martyrs” series by Ghazaleh Rezaei

Author: Anahita Ghabaian

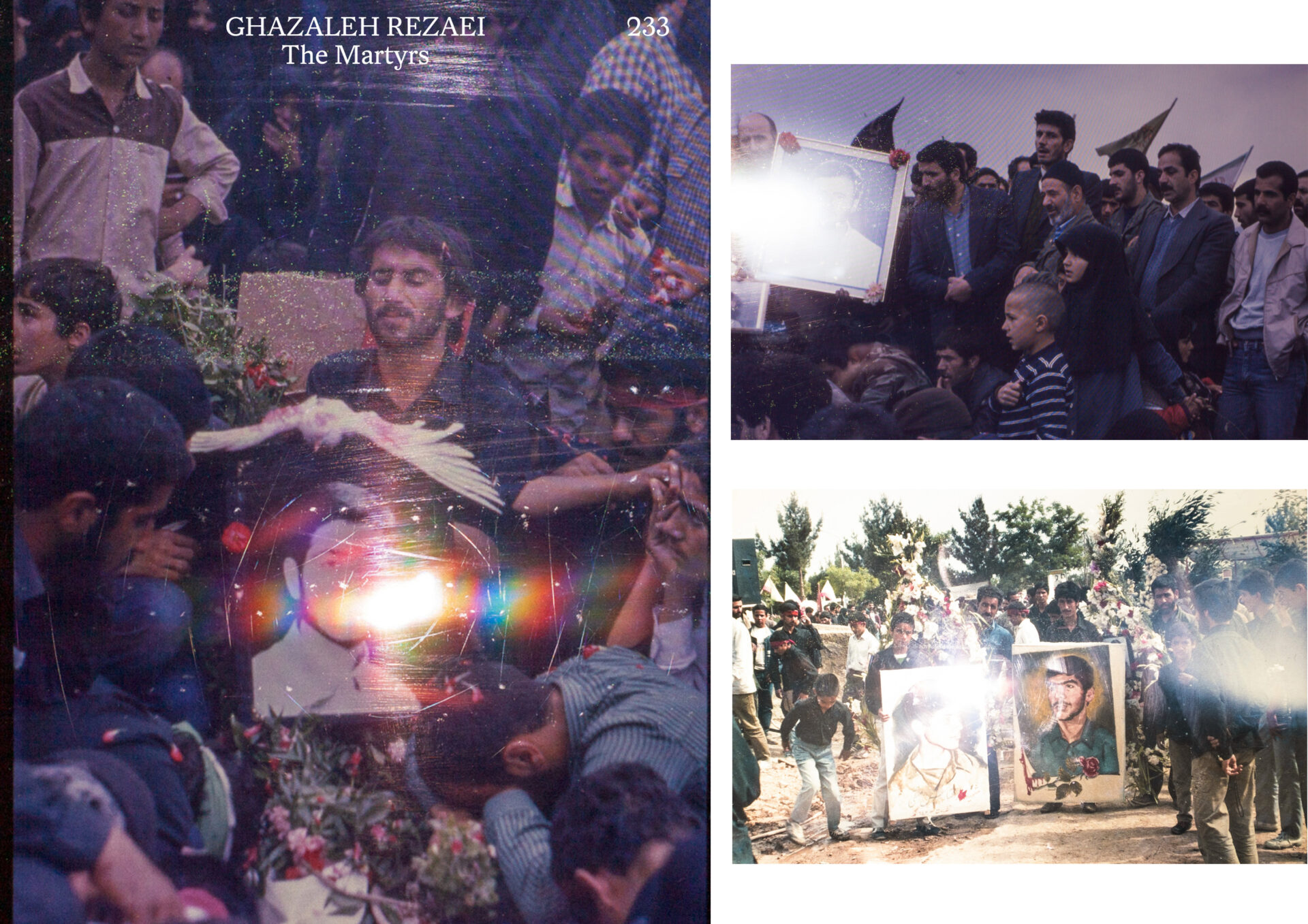

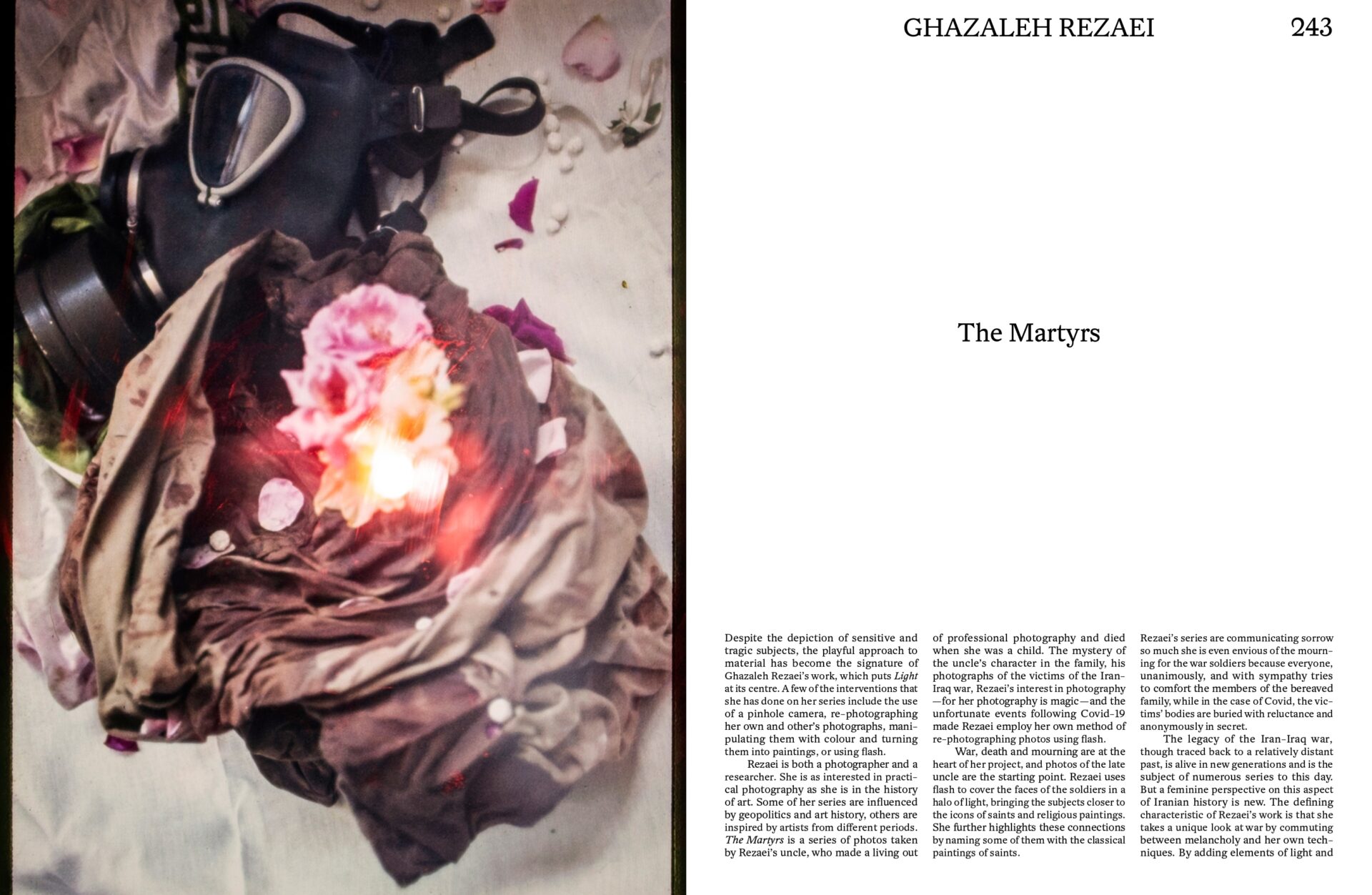

Despite the depiction of sensitive and tragic subjects, the playful approach to material has become the signature of Ghazaleh Rezaei’s work, which puts Light is at its centre. A few of the interventions that she has done on her series include the use of a pinhole camera, re-photographing her own and other’s photographs, manipulating them with colour and turning them into paintings, or using flash.

Rezaei is both a photographer and a researcher. She is as interested in practical photography as she is in the history of art. Some of her series are influenced by geopolitics and art history, others are inspired by artists from different periods. The Martyrs is a series of photos taken by Rezaei’s uncle, who made a living out of professional photography and died when Rezaei was a child. The mystery of the uncle’s character in the family, his photographs of the victims of the Iran-Iraq war, Rezaei’s interest in photography – for her photography is magic – and the unfortunate events following Covid-19 made Rezaei employ her own method of re-photographing photos using flash.

War, death and mourning are at the heart of her project, and photos of the late uncle are the starting point. Rezaei uses flash to cover the faces of the soldiers in a halo of light, bringing the subjects closer to the icons of saints and religious paintings. She further highlights these connections by naming some of them with the classical paintings of saints.

In her other series, Still life with a photo, the photographer uses a ‘mise en abyme’ to refer us to an image. The image indicates an arrangement made by the photographer’s uncle on the occasion of the loss of his brother and his close friend. The very small image is placed next to a photo frame and reappears several times, and over time, with reference to the concepts of martyrdom and loss. Painting and collage have been conducted on them. Rezaei’s series are communicating sorrow so much she is even envious of the mourning for the war soldiers because everyone, unanimously, and with sympathy tries to comfort the members of the bereaved family, while in the case of Covid, the victims’ bodies are buried with reluctance and anonymously in secret.

The legacy of the Iran-Iraq war, though traced back to a relatively distant past, is alive in new generations and is the subject of numerous series to this day. But a feminine perspective on this aspect of Iranian history is new. The characteristic of Rezaei’s work is that she takes a unique look at war by commuting between melancholy and her own techniques. By adding elements of light and colour and photographing the computer screen with elegance and suggestion, she tries to cover up the awkward part of the war, which is in fact an integral part of any war. In no photo the image of a soldier’s lifeless face is seen, and in the painful face of the mourners there is solidarity and tenderness. In fact, it seems that The Martyrs is made to honour the great soldiers of the Iran-Iraq war, as well as her lost uncle, with whom she shared the love of photography.

Like much creative photography within Iran, this work explores ideas of self-expression within society. Managing to apply the direct immediacy of its lens, while still retaining its artistic gaze and composition, contemporary photography delves into the depths of modern Iranian society, revealing and recontextualizing its multilayered aspects. However, Rezaei’s The Martyrs also discloses the inner world of the photographer herself. This series, then, centered upon light, allows the photographer to play the new-yet-familiar game of showing and hiding, revealing and dissembling.

Leave a reply