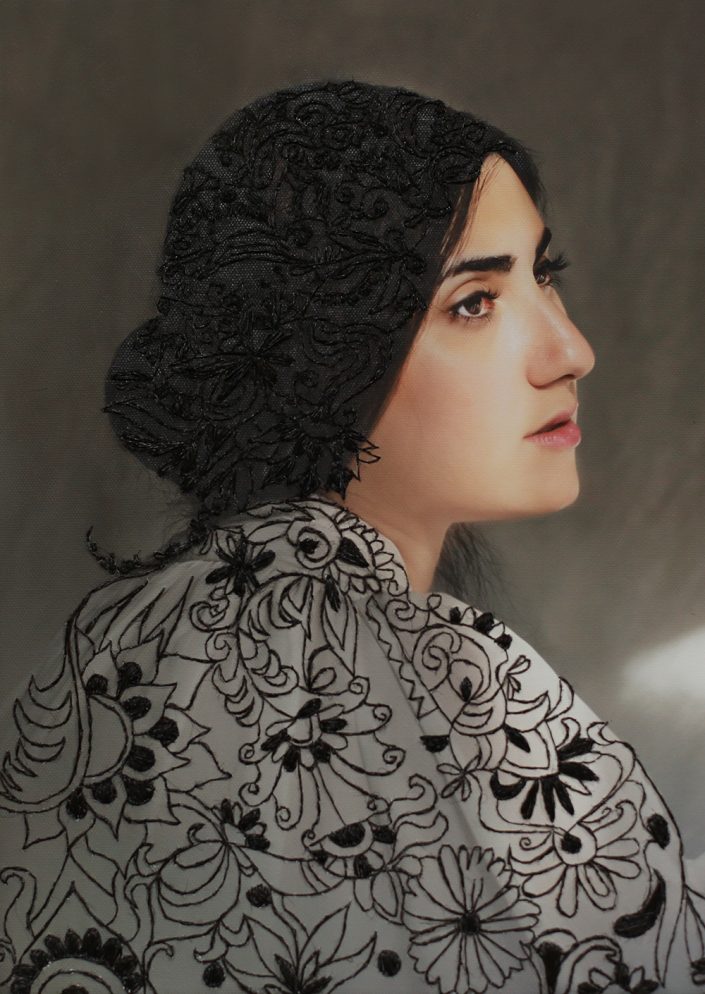

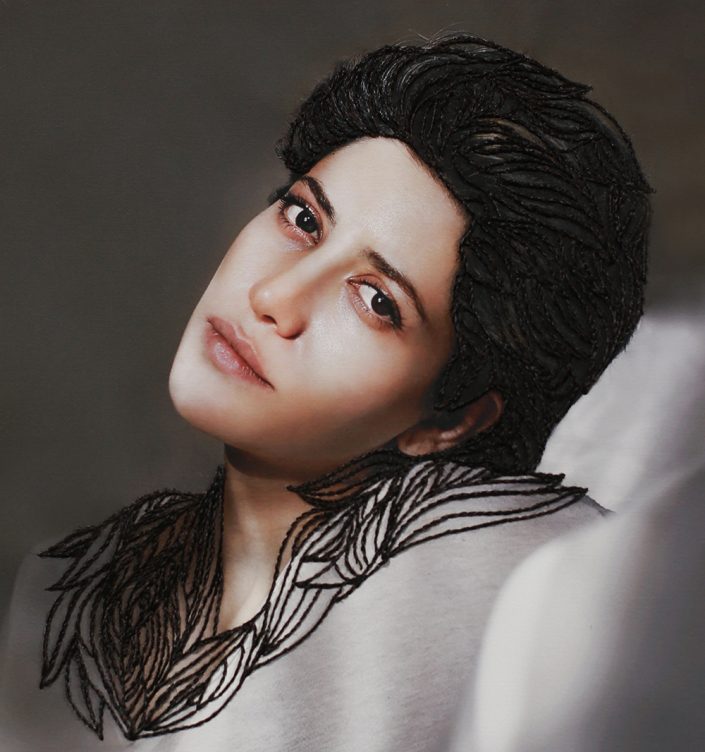

Gisoo, 2017-2020

Maryam Firuzi

Gisoo

Hair is the last organ of the human body to decay. Still, the most impressive image I have ever seen is the piles of hair from the Auschwitz victims in the Polish Museum; hair becomes the embodiment of the souls that are still alive in the strands.

From myth to literature, from popular culture and fairy tales to social punishments, the role of hair is evident, and among all these, the connection between hair and mourning is still special and customary in many tribes; in the Bakhtiari societies, women still cut their hair, and girls shave their heads when they lose the loved ones. This ritual was common between Easterners and Westerners; in Shahnameh, Farangis cuts her hair in mourning for Siavash, as same as Achilles who cuts his hair out of grief over the death of his close friend. In mystical literature, hair has different functions, both material and spiritual. But Hijab and the covering of hair among Iranians have deep roots in history; even today women are forced to cover their hair in their identity photos. Paradoxically, in Islamic law, when the hair of a woman is cut, Hijab would not be anymore an obligation; it is as if the hair which was once an ornament on the woman’s face has become a dead organ and is no more seductive or desirable.

For me, hair is like the threads of the soul, whether over the shoulders or being cut from the heads. I asked my dear friends to stand in front of the camera and then give me their hair to sew them on their printed photos, or cover their bare head with their hair and recapture them. Hopefully, the spirit of the image and the spirit of the subject are reconnected in this process, and what itself causes censorship turns into a device to resist the censorship.

Contact Details :